When to join a startup

Learning to assess risk will help you maximize the economic outcome of joining a startup

When a startup is first founded, it is nothing but risk. Successfully building a company is the act of slowly eliminating that risk until you have created a reliable cash flow machine.

There are five types of risk:

Technology risk - can we get the product to work?

Market risk - can we build something people love?

Scaling risk - can we acquire lots of customers?

Business model risk - can we serve customers profitably?

Defensibility risk - can we maintain market share?

Remove all of them, and a business will become one of the most successful in the world, worth billions of dollars.

YC’s motto is “make something people want”, which is a great objective for early stage startups. The longer term goal is more of a mouthful:

VCs think about risk all the time. When a form of risk is removed, the expected value of a business goes up massively, so it’s lucrative to be the first money in after it’s clear that will happen.

But not enough potential startup employees think about risk, even though it is the #1 thing that determines their economic outcome.

Let’s look at each form of risk and the questions you can ask to understand if they’ve been solved. Then we’ll explore how this typically plays out over a startup’s lifecycle, and what the good entry points are for those considering joining.

Technology risk

Solving technology risk means answering the question “Does this product actually do the thing we want it to?”

Many people who have been in tech for less than ~20 years have never really had to think about this, because most companies were applying existing tech to new problems and customers. Basically every SaaS, marketplace, and e-commerce company jumps right to market risk.

But new waves of technology bring back tech risk. With the rise of AI, many people are joining startups where technology risk is not actually solved, perhaps without even realizing it. Despite the hype, it remains to be seen to what extent and in what situations a model can actually replace a customer support agent, a developer, or an attorney.

Market risk

Solving market risk is often called finding product-market fit, and it is the canonical thing that early stage founders are searching for.

Understanding if a business has hit product market fit is classically fuzzy and sometimes gets summarized as “you’ll know it when you see it”.

However there are two things that are very strong indicators, especially when taken together:

Do customers obviously love the product? Do they talk about how much they love it with their friends? Would they be very upset if it was taken away?

Does the product have strong retention? Specifically, if you draw a survival curve which charts the percentage of customers in each cohort that remain active over time, does it flatten out at some point? The fact that it flattens is more important than where it flattens - some subset of customers must be finding value and sticking for a long time.

Scaling risk

Product market fit often kicks off a wave of organic growth, but it won’t be sufficient to achieve real scale. The next phase is figuring out how to bring a product to many more people.

The thing to look for to assess whether scaling risk has been removed is, well, scale. But more precisely, two things:

Is there at least one channel of growth that is large and can grow reliably in the future? There aren’t many options - in this piece, Lenny and I wrote about how for consumer companies, there are basically only three (virality, paid marketing, and SEO). For B2B businesses you can add sales. One of these channels needs to be absolutely cranking and have a path to continued growth.

Is there a large enough market to continue to grow? This can be hard to assess because the best startups expand their markets and grow into new ones. But even once the business has produced meaningful scale (20, 50, 100 million in revenue) they should probably be less than 5% penetrated in their core market.

Business Model risk

Solving all of the previous forms of risk is considerably easier if you’re selling dollars for 90 cents. The next big risk is figuring out how to actually make money selling something people love.

The best two questions to assess the potential for good economics are:

Does the business have sufficiently low payback periods on customer acquisition spend? Good paybacks are usually about 6 months for B2C companies and 12-18 months for B2B.

Does the business have a healthy contribution margin? Contribution margin is the amount left after you take out all of costs that can be attributed to a transaction, like COGS and marketing. These vary widely but for technology businesses should generally be north of 50% of revenue.

Defensibility risk

Companies that solve for the other forms of risk will inevitably attract a lot of competition. Some businesses will hold up well to this, and others will get locked into a zero sum battle that destroys their margins.

The difference is defensibility, and the best framework I’ve found for understanding this is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. It outlines the way that businesses can continue to earn differential returns, i.e. protect their position.

It’s worth just reading his book. However one shortcut: most defensibility for new technology companies derives from one of three things:

Network effects: does the product get more valuable as more customers use it?

Scale economies: does the cost to serve customers get significantly lower as the business gets larger?

Switching costs: once they have started using the product, is it hard for customers to switch to a similar one?

The journey

Solving for these risks is of course less linear than I’ve presented here. It’s not always clear if a form of risk has actually been removed, and companies can bounce between stages.

In particular, there is often a circular relationship between scaling and business model risk. Getting bigger requires pushing into new channels and new customer segments, both of which put more pressure on economics, so companies must vacillate between expanding, figuring out economics, and expanding again.

A typical journey looks something like this:

Funding rounds map to these stages of risk only very roughly, and that is kind of the point: it’s more important to focus on risk than stage. Companies often get funded before risk has actually been removed. This is especially true in hype cycles like the one we’re going through with AI right now, which can create particularly bad outcomes for employees.

When should you join?

The most basic principle is to try to do the same thing VCs do: invest (join) as soon as you can tell a major risk will been removed, before many other people have figured it out. This is of course not particularly easy to do, but even considering risk gives job seekers a big advantage.

It’s common for candidates to flock to a startup that recently got a big new funding round and big new valuation. This is exactly the kind of thing to avoid, because the upside was just built into the value of your equity grant.

Beyond this basic principle, there are two entry points that are often good, and one that is often dangerous.

One very good time to join a startup is immediately after they have solved market risk (i.e. found product market fit). Most companies that achieve product market fit will not ultimately build a sustainable business. However most of them will go on to grow dramatically, which is great for your career and could produce a meaningful economic outcome. And you will almost certainly learn a lot in the process.

The other great time to join is during the messy dance between scaling and business model risk. These businesses are actively breaking out, and a higher percentage of them are on their way to an IPO or other meaningful exit.

It is an especially good time to join if the company has recently made a lot of progress on one of the forms of risk, such as tapping into a new growth channel or making improvements to their unit economics. One or both of these should be leading to rapidly expanding contribution profit.

A typically bad point to join a startup is before market risk is solved, if you’re not a founder. You’re simply taking on almost as much risk as the founders, with much less equity in return.

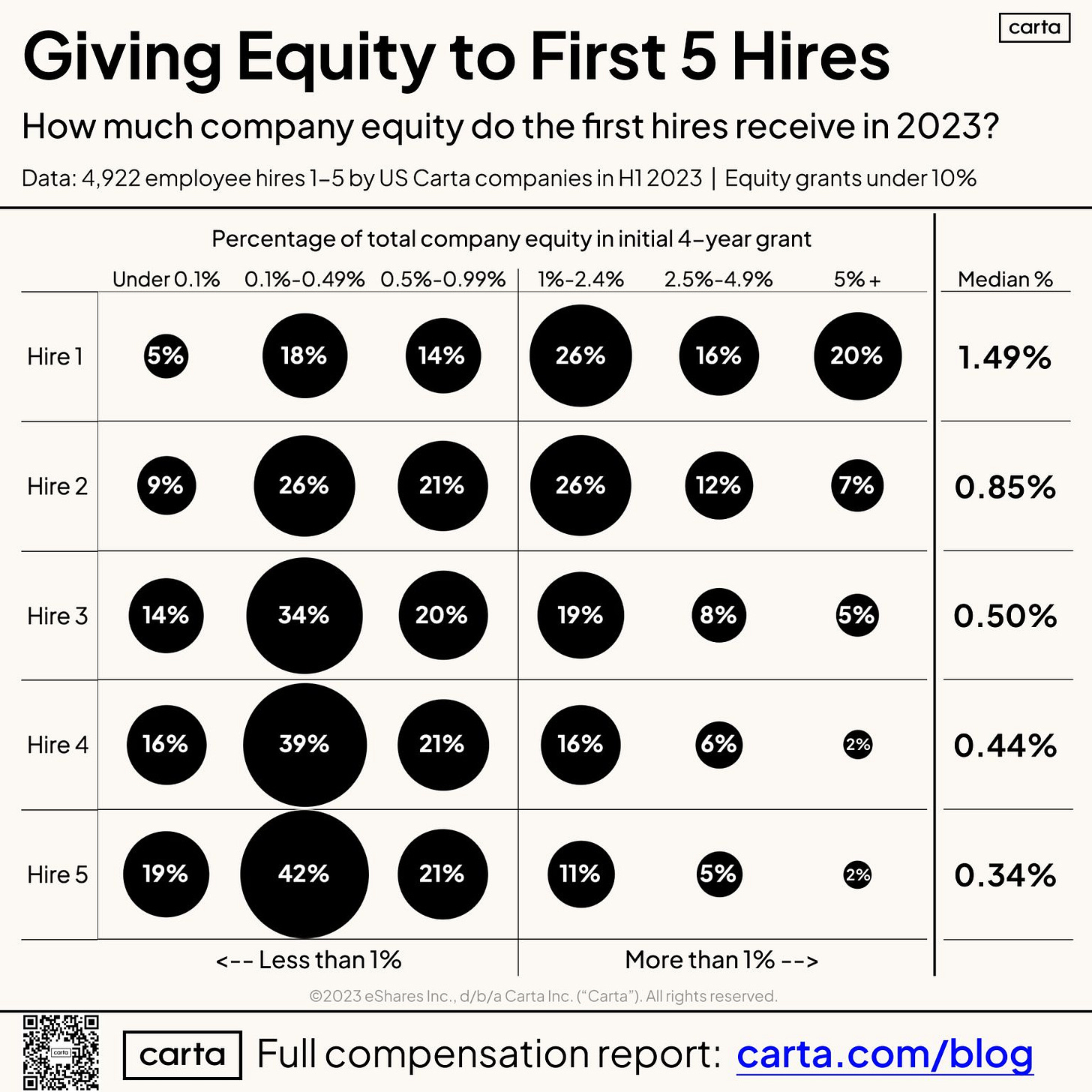

As the table below shows, employees #1-5 usually get around 50 bps of equity, which is at least an order of magnitude less than founders. Are the chances that the company gets to a meaningful outcome also an order of magnitude better? Occasionally, for example in the case of repeat founders who know their market exceptionally well. But not usually.

It might still be a good trade for some people - working on early stage businesses is very fun if you’re wired for it, and it may be a mission you just have to be a part of. But in purely risk vs. reward terms, it’s usually better to wait until the company has found product market fit.

Learning to assess risk

The most important lesson of all: be intentional about learning to assess risk.

Early in a career, that often means working at at least one company that is sufficiently de-risked and sufficiently well run so that you can see what “good” looks like. This will help you get comfortable accepting more risk later on.

Later in a career, it means building enough expertise that you know how to spot breakthroughs in risk before the rest of the market can. That might mean specializing in a stage (such as helping companies scale after they achieve product market fit) or specializing in an industry (such as spending so much time with marketplaces that you know what it looks like as they transition through stages).

Ultimately, the assessment of risk is just one part of a broader framework for how to choose a startup. But if you start thinking a little more about risk and asking some of the questions above as you’re searching, you’re likely to make better decisions.

Credits

Thank you to Casey Winters, Chris Erickson, and Zach Grannis for their feedback on a draft of this essay.

This is a great framework. I get asked about joining startups all the time...

But I NEVER recommend my path (employee #6 of a company that became a $2B public co).

It's not reliable and there is even greater survival risk for early employees than founders (i.e. you are discarded more easily).

I also believe there is far greater variability in how to survive/thrive across multiple stages of a company. It's not just one-startup-experience, there are many layers.

I've written about how the wrong company stage will crush you: https://newsletter.thewayofwork.com/p/stage-fright

Very comprehensive overview. At the end of the day, your investment of time/effort into any new startup should be evaluated with a similar risk/return ratio as any other potential investment.