How to Choose a Startup

And why so many people get it almost entirely backwards

Here is a common failure mode in early startup careers:

Step 1: Get your dream job. Doing product or growth or whatever it is that makes your heart flutter. Great comp, lots of equity.

Step 2: Waste years of your life because the company goes nowhere.

One reason this is so common is that people over-apply lessons learned from big companies where it’s safer to optimize for role and comp because they are more stable. But at a startup, what you do and how much you make can change rapidly and are almost entirely downstream of how well the company does.

I propose a “hierarchy of needs” when picking a startup to join, outlined in the diagram below. Start at the bottom, and only move up when a condition is met. Let’s take them each in turn.

Stage

When someone is considering joining both a startup and Google, it usually means they don’t really know what they want, and that probably what they want is not a startup.

The stage of business determines what game you are playing in the first place: what the job will be like, who will be successful in it, and the mix of risk and reward you are accepting. So start there.

The best framework I’ve found on this topic is from Nikhyl Singhal in Stage of company, not name of company.

He outlines four stages. I split his 3rd stage into two, because I think they can produce quite different experiences. You should be targeting at most two of these stages:

1. Pre-product fit (~Seed - Series A) These companies are figuring out what to build and if people want it at all. They need people who thrive in chaos, can apply a wide range of skills, and need very little hands-on management.

2. Immediately post product fit (~Series B) These companies are turning an initial spark into a real business. They often need people with some functional expertise (product, marketing, ops) to instill best practices for the first time.

3a. Early growth (Series C-D): These companies are experiencing explosive growth. Everything breaks every 6-12 months as a new stage of scale is achieved, so they need people who eat complexity and build process.

3b. Late growth (pre-IPO to immediately post-IPO): These companies are growing fast but starting to show signs of slowing. They need people who can instill discipline as they prepare to go public, but they also need people to help seed new growth bets like geographic expansion or moving upmarket.

4. Scale (FAANG, Microsoft, Salesforce, etc.): These companies are stable and more focused on defense than offense. They need people who thrive in structure and know how to get things done in a more bureaucratic environment.

There is no right or wrong answer. It’s mostly about the kind of environment you will thrive in (more or less guidance, higher or lower rate of change) and the level of risk you’re willing to take.

However a word of caution: if you find you are inclined toward the earlier part of this spectrum, watch out for the danger zone between the founding of the company and product market fit.

If you are not a founder but join a company without product market fit, you’re often taking on a similar level of risk as the founders, but with much less of the upside. As employee #1-5, you’ll likely get in the range of 50 bps of equity, at least an order of magnitude less than founders. That might be an OK trade for some people. But in my view it is often better to either be a founder or wait until the company has found product market fit.

Team

Aside from stage, everything is downstream of the quality of team: how successful the company will be, what your experience will be like working there, and the relationships you build that will serve you later in your career.

Here are three lenses through which to assess the team:

The founders

In this essay, Paul Graham identifies five traits that YC looks for in founders: determination, flexibility, imagination, naughtiness and friendship. It’s about as good as you can do on this topic and it’s short, so I’d suggest just reading it.

Perhaps it goes without saying, but founders are usually pretty intense. It can be harder to relate to them in the same way that you relate to the rest of the team. Before taking that as a negative signal, consider that it might be a good thing: doing extreme things requires extreme traits. Elon Musk in his opening monologue on SNL:

“To anyone I've offended, I just want to say: I reinvented electric cars and I'm sending people to Mars in a rocket ship. Did you think I was also going to be a chill, normal dude?”

The team

Here I’d start with Warren Buffet’s quote on the traits he looks for when hiring: integrity, intelligence, and energy. They are all important, but as Buffet notes, the first is critical:

“Somebody once said that in looking for people to hire, you look for three qualities: integrity, intelligence, and energy. And if you don't have the first, the other two will kill you. You think about it; it's true. If you hire somebody without integrity, you really want them to be dumb and lazy.”

It can’t just be a few people that stand out on these traits, it has to be most of the team. Talent density matters a lot because great people want to work with other great people, and if there aren’t enough of them, they’re ultimately going to leave.

The culture

The only advantage that startups have over incumbents is that they can move faster. As a result, the most important aspect of startup culture is that it enables velocity. This means a culture that is good at making decisions rapidly, and good at course-correcting when those decisions are wrong. It means a culture that has a low degree of politics and bureaucracy for its scale. And it means a culture that operates transparently, allowing everyone in the org to act autonomously.

A few questions to ask to assess culture:

When was the last time two leaders disagreed? What did you do and why?

Tell me about a bad decision you made. Why did it happen? How did you course correct?

What decisions will you expect me to make? Who needs to review my decisions?

Metrics

If you’re fortunate enough to join a company that takes off, your equity will become valuable, so comp is mostly downstream of company performance. And the team will scale rapidly giving you bigger jobs and more optionality, so role is mostly downstream of performance as well.

While you’ll want to consider more than these, here are four metrics that collectively do a very good job of assessing the quality of a business:

1. Retention

Retention is by far the most important metric because it is both the best indicator of product market fit and the driver of all other metrics. Look at both user retention (how many customers are still active after x months) and revenue retention (how much revenue a cohort produces relative to its first year). You can find good benchmarks on both from Lenny Rachitsky here.

2. Growth rate (especially “natural” growth)

Here are more good benchmarks from Lenny on growth rate by stage:

While harder to benchmark, more important than aggregate growth rate is the “natural” growth rate, net of paid marketing and SEO.

Paid marketing and SEO can be important ways to grow, but they can also be influenced by marketing budget and content, and they are not entirely in a company’s control. A product manager at Google can wake up one morning and decide to run an experiment that tanks your traffic. What is left without these two channels is organic and viral growth, which tells a story of natural pull from the market: how fast are users finding and telling others about the product?

3. Unit economics

This is particularly relevant for transactional businesses like marketplaces, but don't just assume SaaS businesses have great economics. In particular, focus on contribution margin, which answers the question “how much is left after you take out all of the direct costs of a transaction?” More on how to calculate contribution margin from CJ Gustafson here.

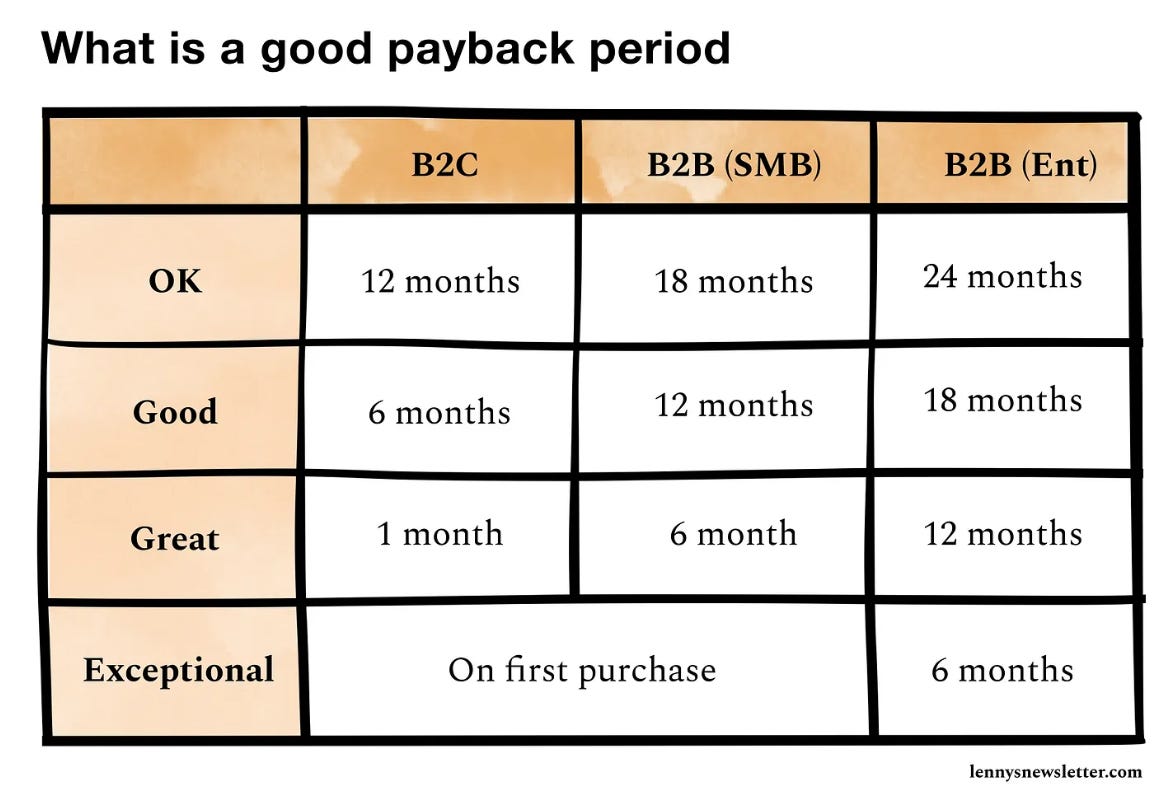

4. Payback period

Payback period (the amount of time it takes for an acquired customer to produce more contribution margin than the cost to acquire them) is the best measure of customer acquisition efficiency, because it measures how quickly marketing spend can be re-invested in more growth. Benchmarks from Lenny here.

Role

Startup roles are much more fluid than big company roles. It’s unlikely you’ll do the same thing for very long, especially if the company is highly successful.

So instead of focusing on a specific function or team, optimize for a role that will allow you to maximize your impact, and put up wins quickly to open up your options within the company. This comes down to basically three things:

What you are naturally good at. The main failure mode here is getting distracted by what you think you “should” be doing. Many people genuinely love and are great at product management, but many others flock to it because it’s the “cool” job to have. The more you can ignore this kind of thinking, the better off you will be.

Where you have expertise. Over time, the way to get real career leverage and produce outsized impact is to specialize (2). You could specialize by function (product vs. marketing vs. ops), or stage (product fit vs. growth), or type of business (marketplace vs. saas vs. hardware). Often the way to be exceptionally valuable is to combine multiple of these that are rarely combined.

What the company needs. Finally, map what you’re good at to what makes the company tick. This is mainly a product of:

Company stage: refer back to that step.

How the company grows: I’ve seen many traditional marketers get frustrated at companies for which growth is almost entirely product-led and the marketing team is starved of attention and resources. Or product managers who are frustrated at sales-led companies.

How the company makes decisions: If you are a data person, join a company that is data-driven. Don’t join a company that doesn’t value data and try to convince them otherwise, because you will likely fail. Similarly, consider the difference between writing cultures and presentation cultures and where you’re more likely to be successful.

A final note: I’m talking only about role, not title. I would explicitly not optimize for title, and probably optimize AWAY from it early in your career. This is why:

Comp

Comp is important and anyone who tells you it isn’t is either kidding themselves or trying to sell you something. It’s important because money is useful and everyone wants more of it. It’s also important because it tells you a lot about the company you are considering joining.

The mix of comp and equity tell you about the stage of the business and how to think about risk vs. reward. And the total size of the package tells you about how much they value you and often something about the quality of the business.

When I was considering my first startup role, I got a few offers from startups that were in the same ballpark, and an offer from a D2C business that was close to half of the others. The fact that this outlier offer was so low was a good sign that we were either misaligned on what I could contribute, or it simply wasn’t as good of a business as the true tech companies I was talking to (and probably both).

So of course it is worth paying attention to comp, and to maximize it when all else is equal. But if you stick with startups long enough, the majority of your comp will come from equity, and that is mostly determined by how well the company does and how well you do within it. That’s why comp is last on the list.

If you are highly intentional about choosing startups using a framework like this one, and give yourself time to take multiple swings, I believe your likelihood of picking one that goes on to grow dramatically is pretty high. Doing that will be an incredible accelerant for your career.

Credits

Thank you to Carla Pellicano, Jolie Zwick, and Lenny Rachitsky for their thoughtful feedback on drafts of this essay.

Notes

(1) Two additional thoughts on metrics:

The metrics discussed here mostly apply at the product market fit stage and beyond. Before that, you’re looking for the potential to achieve this kind of performance, which is harder.

Once you get an offer, a startup should be willing to share all of their numbers, so you should have pretty good data on which to evaluate these metrics. If a startup isn’t willing to go open book on their numbers, that is a red flag.

(2) My main advice on expertise is to not fall into the trap of remaining a generalist for too long. Here is something I wrote on this trap: Generalist Disease

I think your point about stage of the company and its changing needs is fascinating. As a consultant, we occasionally advice on the right hire for organisations in our niche (often big tech).

I'm curious about your take on the idea that many, if not most, people at startups tend to be mercenary in nature - jumping from one organisation to the next. In Europe, we often think of employees in the USA as contractors rather than employees. They can be terminated at will and they seem to change jobs every 2 to 3 years (some a lot sooner).

Do you see this reflected in the startups you're discussing here?

This is the exact right take on whether or not someone should be joining a startup and what they should pay attention to. I get this question all the time from people thinking about "trying out" working at a startup. It's simply not for everyone and that's fine. Moreover, it MIGHT be something that's fit for you, but not that specific company due to the stage they're at. That's a unique perspective that I hadn't quite considered.