Why Did DoorDash Win?

The business school version of why DoorDash won is that they had the right strategy. They launched in the right markets, acquired the right restaurants, and designed the marketplace the right way.

The Silicon Valley hustle culture version is that they out-executed everyone else. They just shipped faster until they had better selection, a better product, and more reliable delivery.

The financial markets version is that they got lucky. Grubhub and Uber were both public and playing with a hand tied behind their back during the most pivotal moment in the fight.

The reality is that you can’t understand what happened without all three perspectives. Increasingly, success in every competitive market will require the right strategy, rapid execution, and good luck.

Strategy

Strategy turns on a few big decisions. For DoorDash, three of them really mattered.

The first was recognizing that owning delivery was the key to unlocking supply. Most restaurants can’t support the economics of running their own delivery fleet, so the Grubhub model of just routing orders to restaurants was bound to hit a wall.

DoorDash was the only company that launched with the business model that everyone now uses. The initial idea for Uber Eats was to load cars with fresh meals made at scale so they could be delivered as fast as possible. Postmates started with packages, not food.

DoorDash recognized the importance of logistics from the start. This was CEO Tony Xu’s final slide at YC demo day in 2013:

The second big decision was seemingly at odds with the first. Rule #1 of building a logistics business is to increase network density and thus driver utilization. This led everyone else to major city centers.

But DoorDash realized the suburbs were a better place to start. There, the alternatives to delivery were much worse, customers were more affluent, and average order values were higher. Customers immediately understood the value prop and spent enough to make delivery economics work.

Most importantly, no one else was in the suburbs yet. This is a key principle in Sarah Tavel’s Hierarchy of Marketplaces:

To win in a market, you can’t just be the market leader. You have to be the market leader by a lot. This creates a flywheel in which you have much more demand, which allows you to bring on more supply, which in turn compounds your demand advantage. Every market in food delivery was ultimately hard fought, but DoorDash’s initial wedge in the suburbs gave them an advantage no one else had.

Finally, DoorDash recognized that the most important thing was a wide selection of restaurants, even if that meant sacrificing other things that customers cared about, like delivery speed and price.

They realized that as long as they could deliver in about 40 minutes, there were limited gains from being faster. Uber tried to optimize for faster delivery, which led to the wrong decisions, including launching with the wrong business model in the first place.

DoorDash was also willing to initially make the service more expensive for consumers, which allowed them to give commission breaks to important restaurants to convince them to join. Uber instead wanted a flat customer fee, which required them to play hardball with restaurants. Later, DoorDash did begin to win on price (in particular through DashPass and lower markups on food items), but only once they had great selection.

Execution

DoorDash had the right strategy, and still almost failed.

They exploded out of the gate, raising a Series A from Sequoia in 2014. Legendary investor John Doerr effectively came out of retirement to lead their Series B in 2015 at a $600M valuation.

But then the music stopped. They were burning cash fast, and Tony couldn’t find a lead for their next round for six months. In 2016, Sequoia ultimately had to step in and lead their Series C at a $700M post-money valuation—a down round. By the end of 2017, they were almost out of money again and had to do a $60M bridge round just to keep the company alive.

Uber and Grubhub had much deeper pockets during this time. DoorDash only survived through incredible speed of execution.

The culture starts with Tony and the leadership team he built. Execs like Prabir Adarkar (President and COO), Keith Yandell (CBO), and Jessica Lachs (CAO) are cut from the same cloth - relentless, data-driven, and capable of operating at the lowest level of detail.

They learned to do many things at once. This is Keith Yandell on the Crucible Moments podcast:

People would come in and say, “Well, do you want to focus on growth or do you want to focus on profitability?” And we quickly realized that if we were going to survive this time, we had to do both at the same time. Eventually, we just made it a core value. It’s “and,” not “or.” You can’t pick or choose. We must grow, and we must become more profitable.

This speed translated to better metrics, but also to a better customer experience. Most customers in the early days of food delivery would switch between apps, but eventually became loyal to DoorDash.

When you ask them why, you hear things like “It was just more reliable”. The ops team focused on making deliveries a little faster and reducing defect rates every week. They scrutinized the quality of every one of their restaurants and dashers.

Or you hear “The app was just better”. The product team made sure it was easier to use, less cluttered, and the checkout was faster. The photos were bigger, it was easier to select items, and easier to re-order what you had last time. They were first to let you see where your dasher was so you knew when you were going to get your food.

They launched DashPass before Uber launched Uber Rewards. They launched the Chase Sapphire partnership before Uber launched the Amex partnership.

All of this added up to better and better customer retention, and markets began tipping in DoorDash’s favor.

Luck

By 2018, the business was on track to be a great outcome, but a little luck ensured it became a monster one.

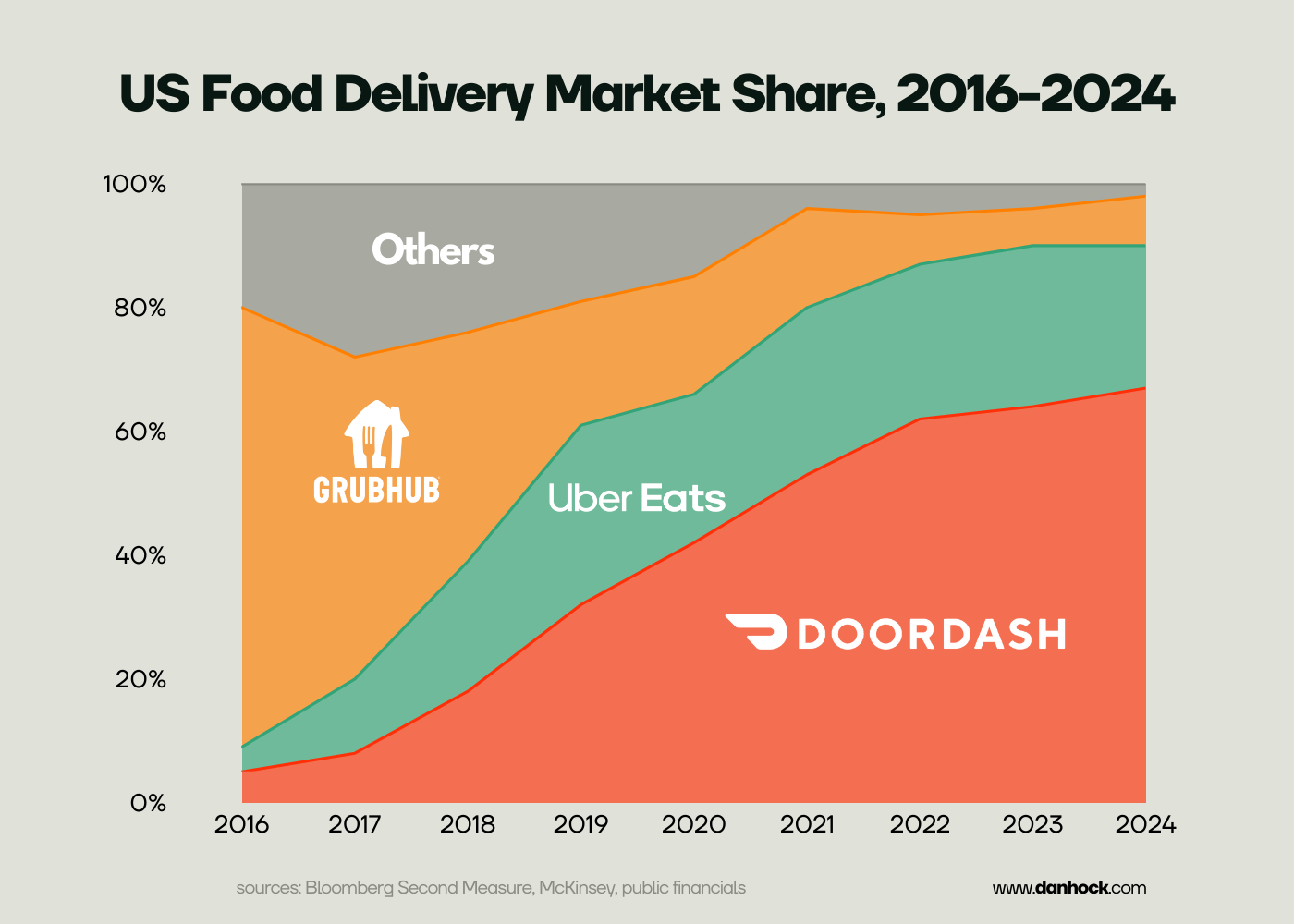

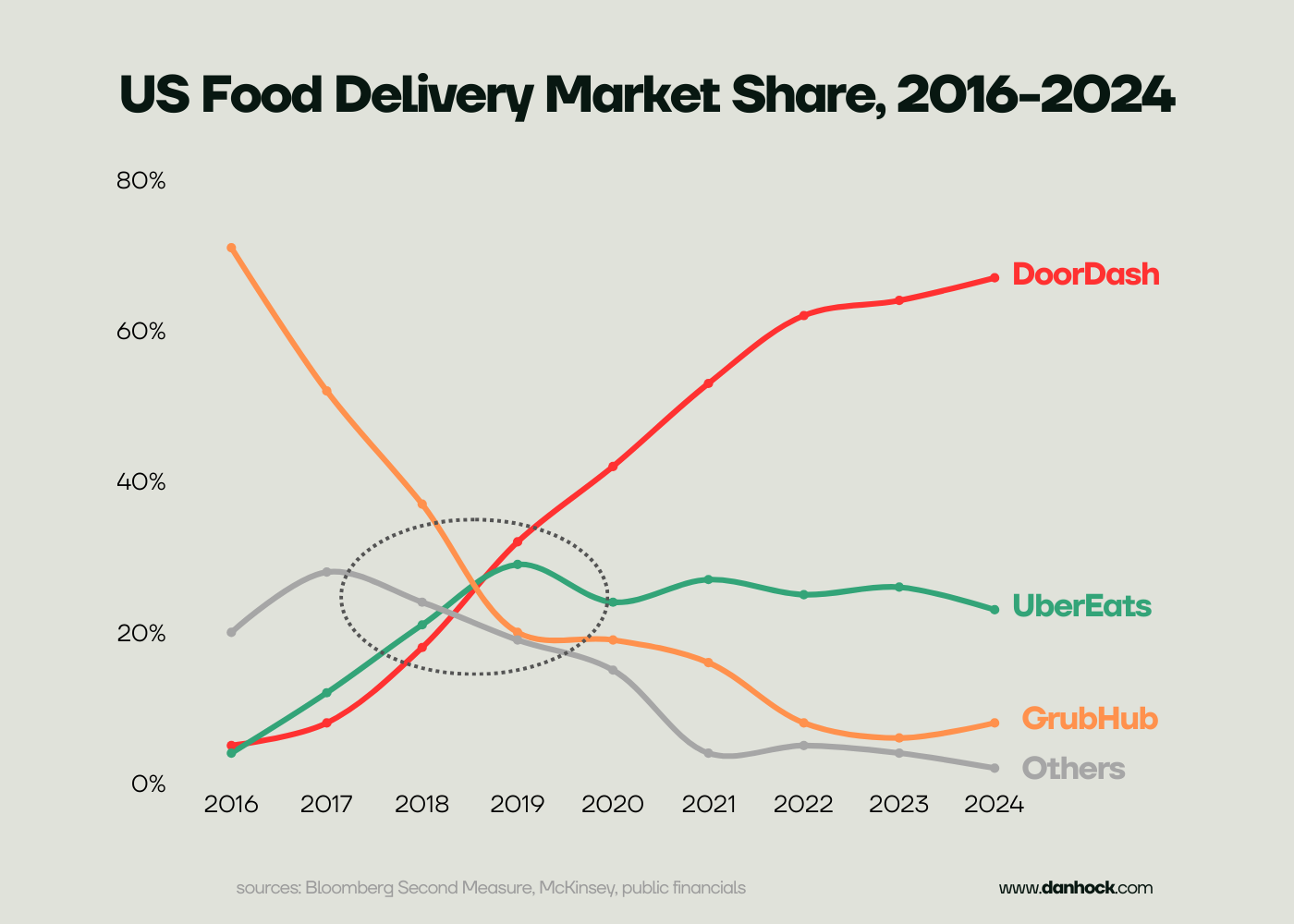

The period from 2018-2019 was the most crucial, because it determined the footing each company was on going into the pandemic, when food delivery demand soared.

What was happening during this time period? Grubhub was already public, and CEO Matt Maloney had sold the markets on an efficient, asset-light model, a position he would continue to double down on as late as 2021:

“[Food delivery] is and always will be a crummy business”. Everyone else in the industry is doubling down on their logistics plays and talking about how smart they are and what a great technology company they are. I think the right choice is to be a better restaurant company.”

It would have cratered their market cap to take on the burn required to pivot to DoorDash’s model. Instead, they stayed asset-light and posted EBITDA margins of 14% ($186M on 1.3B in revenue).

Uber was recovering from #DeleteUber and a CEO change. They went public in May 2019, which forced them to cut back on their famously high burn. The combined business had EBITDA margins of -19%.

Meanwhile, DoorDash let it rip. They raised $535M from Softbank in 2018, another $250M later that year, and $1B across two rounds in 2019. In 2019 they lost $475M, a whopping -54% EBITDA margin.

They leaned heavily into market launch (including 5x-ing their market footprint in 2018 alone) and into customer acquisition, including running major brand campaigns. From 2019-2021, DoorDash spent more than $3 billion on marketing and sales.

This catapulted them from a distant third in 2017 to the market leadership position in March 2019. As the world shut down and food delivery became critical infrastructure in early 2020, DoorDash capitalized and compounded their gains.

Things might still have gone differently had Uber been able to acquire Grubhub in 2021 and built a combined business to rival DoorDash. Instead, Uber was outbid by Just Eat, which had no presence in the US and sold the business in 2024 at a loss.

Doordash had the right strategy, shipped fast, and was able to take full advantage of a once-in-a-generation tailwind.

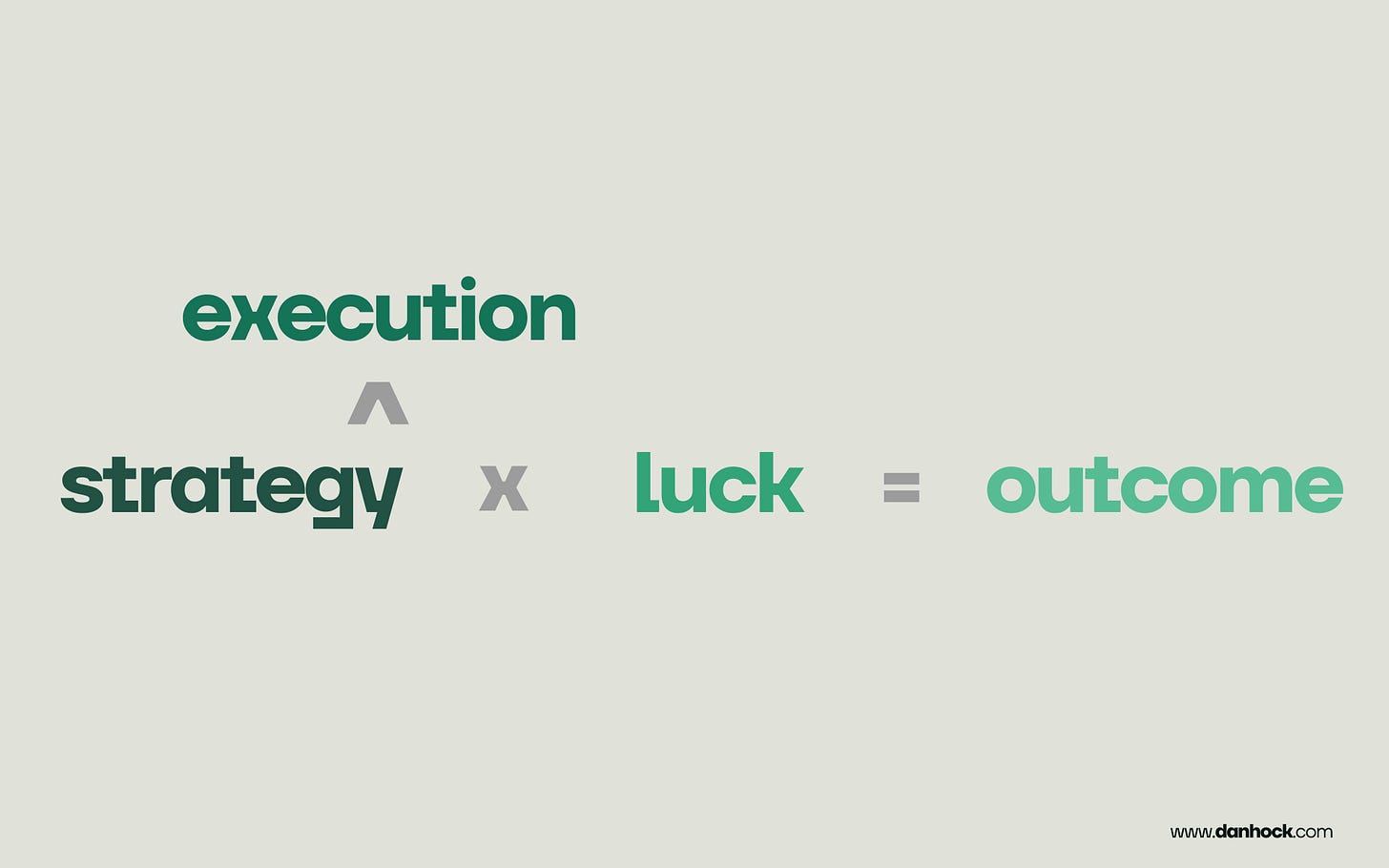

We could formulate a crude success equation as:

The first term must be strategy because without it, you’re running in the wrong direction.

But this is raised to the power of execution velocity. Shipping things is a way to pressure test and improve your strategy. Ship fast, and you’ll quickly find new things that work and compound your gains. Ship slow, and you’ll get passed by competitors, even the ones that started with the wrong idea.

Luck is a force multiplier - a good break will magnify the outcome, and a bad one can turn a company into a zero.

Twenty years ago, it might have been sufficient to have just two of the three. But today, the tools available to startups are better, information travels faster, and venture markets are more liquid. Every big market is going to be full of well-funded, aggressive competitors.

To win, you need to be in the right place at the right time, have the right idea, and still run very fast.

Sources

The Changing Market for Food Delivery - McKinsey, 2016

The Complete History and Strategy of DoorDash - Acquired, 2020

The Hierarchy of Marketplaces - Sarah Tavel, 2020

Food Delivery Wars: 3 Takeaways From The UberEats, Postmates, Grubhub, DoorDash Ecosystem - Sarah Tavel, 2020

DoorDash from application to IPO - Paul Buchheit, 2020

Thread on why Doordash won - Michael Bloch, 2020

DoorDash and Uber Eats Are Hot. They’re Still Not Making Money - WSJ, 2021

Ordering in: The rapid evolution of food delivery - McKinsey, 2021

DoorDash ft. Tony Xu – The “Wrong” Moves That Built a Giant - Crucible Moments from Sequoia, 2024

Which company is winning the restaurant food delivery war? - Bloomberg Second Measure, 2024

DASH, UBER, GRUB public filings

Great post! What strikes me in the execution piece of it, is that Doordash could focus on just food delivery while Uber had multiple business line focuses. I don't know how important that was but from conversations with Uber employees I think the prior assumptions from ride share didn't carry over to food delivery.

Really interesting write up, thanks Dan! Even with the evidence you have provided, the suburban play sounds so backwards to me. I have always assumed that the majority of the earnings come from urban centers where it can be more difficult to travel to get the food yourself. With how much these services cost to use, as a consumer I still find it difficult that they turn a profit, but I am obviously proved very wrong here.