The Unbundling Fallacy

When capital flows like water, many ideas seem like great standalone businesses. A 13-year bull run led to predictions of the unbundling of Craigslist, Facebook, Ebay, LinkedIn, Reddit, and many others.

The narrative goes like this: the incumbents are fat and lazy, and under-serve their various niche audiences. This makes them vulnerable to startups which can better serve those niches, sharding them into a million pieces, or at least into many unicorn-sized pieces.

However, most of the unbundlers fail, or are occasionally swallowed back up by the businesses they were supposed to disrupt. Of course there are notable successes, but they don’t seem to be all that common.

Josh Breinlinger has a good post about how Craigslist spawned many fewer large businesses than predicted. And it is worth noting that even most of the success cases on the right have reached nothing like the scale or profitability we might have expected.

If anything, the natural trajectory seems to be toward more bundling, not less. The universe of public stocks is shrinking.

Why is that? In short, the most efficient business wins, and the unbundlers are usually less efficient.

A good measure of the efficiency of a business is its payback period on customer acquisition: how long does it take for a customer to generate more contribution margin than the cost to acquire them? Payback period determines how efficiently a business can deploy capital, and thus how quickly it can grow. Having a good payback period requires you to convert customers effectively and then retain and monetize them well.

To be a sustainable standalone business, a startup has to figure out how to make its payback periods at least as short as its incumbent competition for some segment of customers. For that segment, the benefits from depth must outweigh the benefits from breath in a way that accrues to increasing LTV or lowering CAC. This rarely turns out to be the case.

The Benefits of depth

There is one common way in which being narrow does materialize. When you’re building for a very specific set of customers, you can often create a better UX than they would get with a more “general purpose” product.

There is almost always some benefit to be gained on this dimension. It is true that you could create a better UX than LinkedIn if you designed it just for architects or investment bankers. It is true that the Reddit community might want to engage on movies slightly differently than it engages on politics.

But generally, this is outweighed by the benefits of breath. The central fallacy in most predictions of unbundling is to anchor on UX and ignore the other factors.

The benefits of breadth

Breadth most frequently improves a company’s payback period in three ways: engagement frequency, network effects, and scale economies.

Engagement frequency - Being broader simply gives customers more opportunity to engage, which leads to more frequent usage and transactions. When I worked at Thumbtack, we had a spreadsheet that tracked hundreds (literally hundreds) of competitors, most of whom were trying to pick off a specific vertical, like dog walking or plumbing. It was hard for them to compete with broader marketplaces like Thumbtack, because we could drive repeat transactions across hundreds of categories, which increased customer LTV and allowed us to pay more for customers.

This benefit is even bigger than it might seem on the surface. If your product has low frequency (say, less than once per month) you have another problem. Your customers will forget about you, and you’ll typically have to pay more to re-acquire them.

Network effects - James Currier of NFX wrote that 70% of value in tech is driven by network effects. As a rule, I take with a grain of salt any analysis of a topic done by a firm named after that topic. But having seen the compounding advantage of network effects up close for many years, I’m inclined to agree with James that the number is quite high.

Network effects come in two basic flavors. Same-side network effects, which we see most classically in a social network, are when each additional user makes the product more valuable for all other users. Cross-side network effects, which we see most classically in marketplaces, are when more supply makes the product more valuable to demand, and vice versa.

One of the key reasons that unbundlers fail is that their network effect is handicapped relative to the incumbent. In the case of same-side network effects, unbundlers are often simply presented with a smaller potential network. This is a key weakness in the premise that Reddit will unbundle. Most users engage in multiple subreddits, and find it valuable to have them all in one place.

Cross-side network effects exacerbate this problem, because often only one side of the network is unbundle-able. If you tried to build the “product designer” version of LinkedIn, you may have a supply side (employees) which stay in one field long enough for them to want such a thing, but a demand side (employers) for whom product designers are only one of the roles they are hiring for.

Scale economies - Bigger businesses are usually more profitable. This may accrue directly to unit economics, as in the case of Amazon using its scale to drive freight costs down. That directly improves payback periods by increasing contribution margin, or can be re-investing to improve the customer experience and lift customer retention, as in the case of their moat around Prime. Or it may manifest in the ability to allocate fixed costs across a broader customer base. Eliminating redundant fixed costs is often a big part of the rationale when an incumbent acquires its attempted unbundler.

What might unbundle?

When we look at the entire picture, it becomes clear why it is so hard to unbundle. And that will become more obvious as the capital that was previously used to brute-force past long or infinite payback periods becomes more scarce.

However, there are cases where unbundling will lead to large, category-defining businesses, and it is worth examining what has worked in the past to develop some criteria for what is to come.

There are two table stakes criteria - without them unbundling is unlikely to be successful, but they are insufficient on their own.

First, customer LTV must be sufficiently high even when carving out a specific vertical to produce, either through high frequency (ride sharing) or transaction sizes (travel)

Second, there must exist some group of customers (or network of supply and demand) with sufficiently limited overlap with other groups or networks, diminishing the benefits of network effects. Better yet, a negative network effect in which one customer group explicitly does not want to be in the same network as another.

The final criteria is the one that actually makes the new business win, and it speaks to the kernel of truth in all of the predictions of mass unbundling. That is, there must be room for a highly heterogeneous mode of interaction that the target group of customers would greatly prefer, resulting in deeper engagement and ultimately monetization.

Because the benefits on the other side of the balance sheet are usually so big, a “little bit better” UX won’t do. This is part of the root of why silicon valley is obsessed with the idea that a new product must be 10x better. (I’m not sure where this first originated, but I believe I heard it first from Bill Gross.)

Let’s look at a few examples of targets to unbundle, and what seems to be clearing the hurdle.

Many people look at the LinkedIn experience, which feels like it hasn’t evolved materially in years, and see a platform that is ripe for unbundling. But there have been many attempts at that, which have mostly failed. It’s incredibly resistant to unbundling, mostly because of its powerful network effect.

However I do think we are starting to see successes in large, relatively self-contained networks which also benefit from a very different UX. A few examples:

Workrise (formerly RigUp) is building for the blue collar segment by going much deeper into the user experience on both sides of the marketplace. They directly handle negotiation of services agreements, manage compliance, and handle payments and invoicing.

Handshake is doing something similar for college students. One of the reasons it works is that there is a legitimately different UX required. The profile page is different, the attributes you want to collect on job seekers and employers are different, and the recruiting and interview experience that you’re funneling into is different.

These are large, self-contained networks that benefit from a very different product experience.

Ebay

The much-predicted unbundling of Ebay never seems to happen, which Ebay addressed directly during its 2022 investor day in the slide below. (Since the creation of this chart, Ebay’s market cap is down by a third, but the collective market cap of its vertical competitors is probably down by more than that.)

Etsy is likely the most successful unbundler of Ebay. Tellingly, it is not actually “vertical” in the classic sense, because it covers a wide range of product categories. What it picked off was really more of the subset of the network which is interested in buying and selling homemade goods, and all of the nuance in UX and marketplace mechanics which accompany that.

GOAT and StockX seemed to successfully carve out the sneaker market from Ebay and have now expanded into apparel and other categories. The key initial unlock was investing in verification to better ensure authenticity. Will this be enough? My hunch is that it is going to be a slog, because these are features Ebay can replicate, and the underlying UX is not all that different.

In contrast, players like WhatNot are increasingly venturing into the same categories but with a wildly different UX, necessitated by live streaming and synchronous selling. My bet is on one or more startups in this space finding an easier path to truly break out and create a sustainable business.

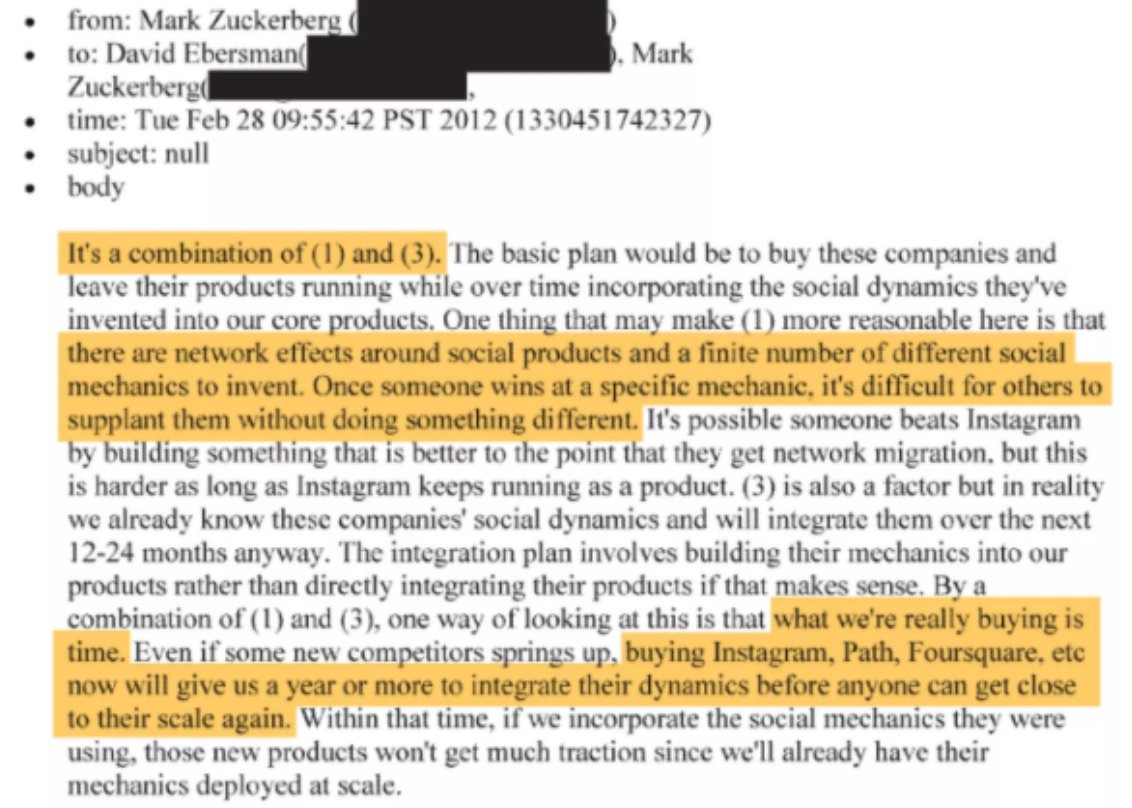

Our criteria also help explain why Facebook has proven less defensible and more dependent on M&A than many other mega tech companies. Mark Zukerberg is obsessed with owning new “social mechanics” - think text, images, disappearing images, and short form video. These unique forms of UX have a tendency to become wedges that allow new entrants to run away with a segment of the market unless they were acquired early.

That is because the benefits of a new kind of UX can be extreme, especially when they collide with a new (usually younger) customer segment for which it feels native. And simultaneously, this younger group is both large and specifically wants a network of its own. It is a perfect storm that opens the gates to unbundlers.

--

Unbundlers will continue to have a path to success, but there are many more win conditions than a slick UX. I'd make sure they meet all of them, especially in our new era of austerity.

Thank you to Casey Winters, Forrest Funnell, Lenny Rachitsky, and Zach Grannis for reading drafts of this post.