The Two Paths of a Manager

Diagnosing and course correcting two of the most common stumbling blocks for new managers

Almost all new managers have one of two failure modes.

The first is probably what comes to mind when most people think of a “bad manager”: micromanagers who get into every detail and undermine the autonomy of their team.

However the inverse problem is at least as common, especially in startups: “macromanagers” who give too little direction to their team and undermine their performance.

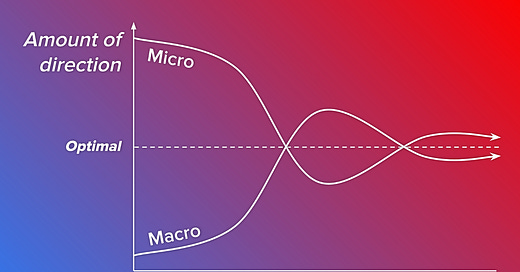

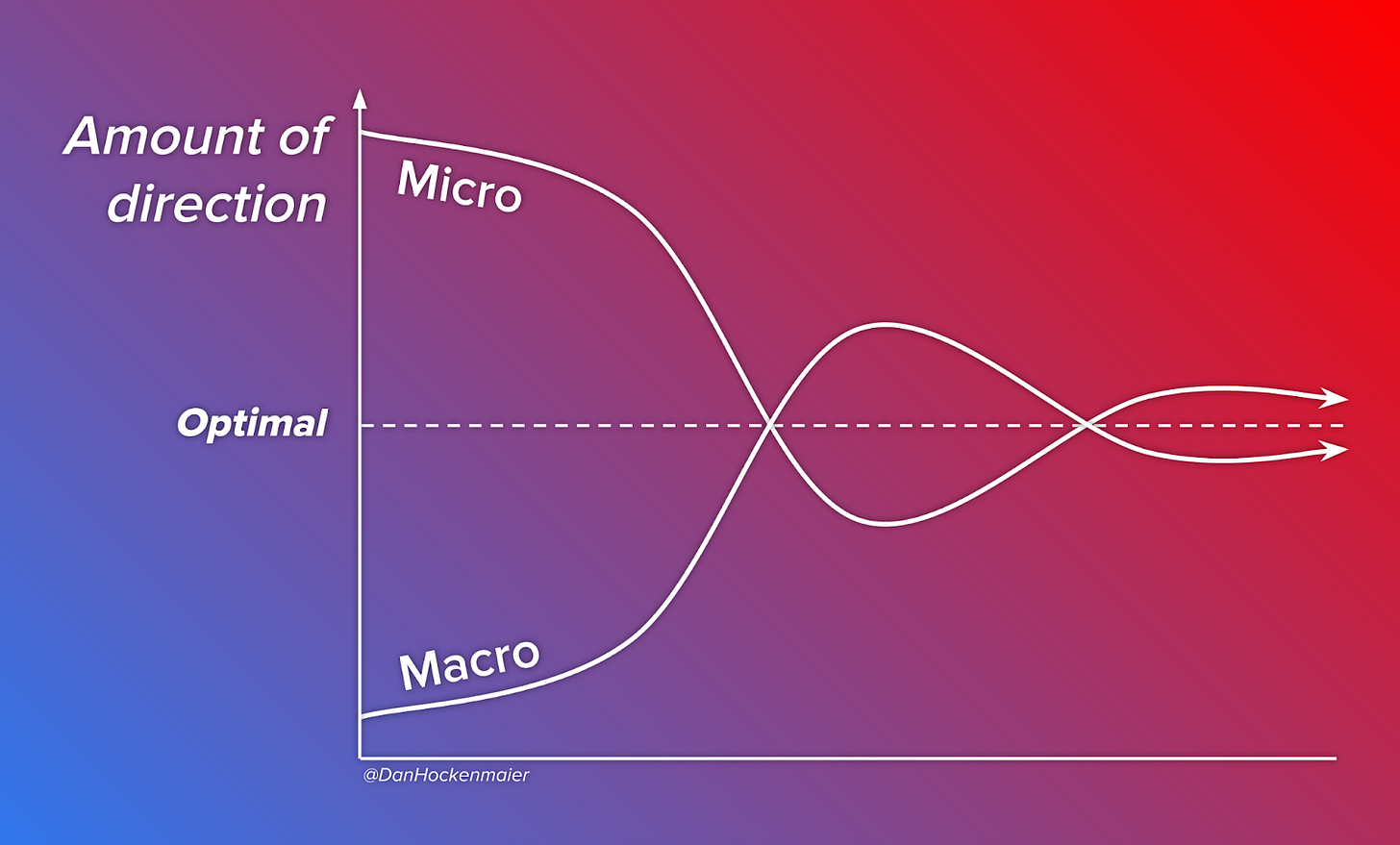

A large part of the journey to becoming a better manager is about correcting (and often over-correcting) until you find the optimal balance. The two paths look something like this:

Too often, managers wait until a crisis to course correct. Micromanagers are usually good at getting results in the short term, at the expense of eroding trust and losing engagement from the team over time. Crises often show up as people problems, like someone quitting without providing enough warning to do anything about it.

Macromanagers initially create happier teams, but they are likely to produce worse results. Crises often first manifest as output problems: the team fails at a project, or gets a reputation for not being able to ship. Over time, teams with macromanagers realize they are having less impact and not learning as much, which results in people problems as well.

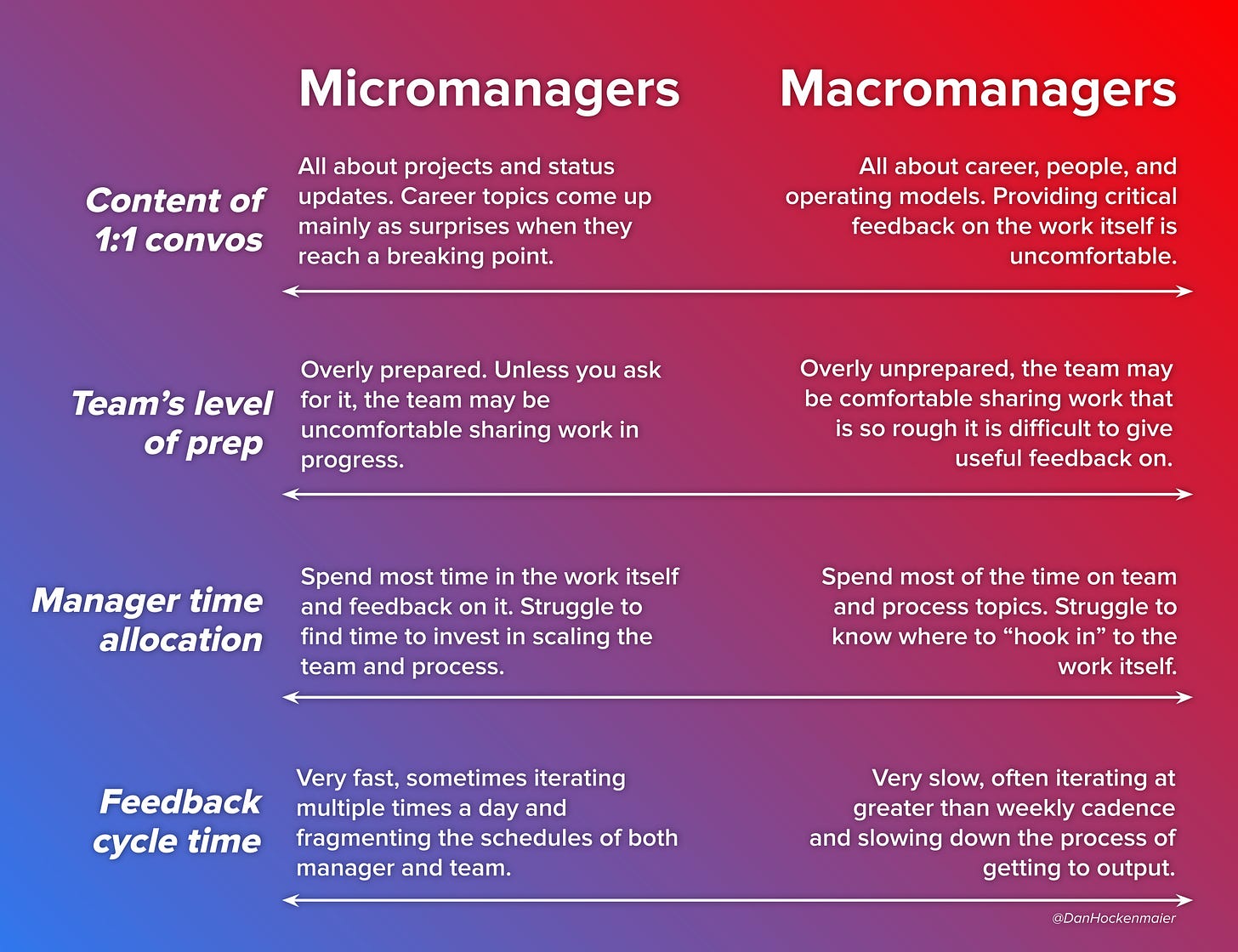

Tuning in to leading indicators can help new managers diagnose the path they are on before it creates a crisis. Here are a few dimensions to consider, and what may manifest on either end:

Course correcting

Once you know the path you are on, here are some steps to accelerate course correction:

Name your fears

Know your team

Apply an intervention framework

Become a context sponge

The first step is naming your fears, because you can analyze the situation all you want, but until you get to the root of what is driving it, it’s too easy to fall back on old habits.

Micromanagers are often afraid they won’t be able to get their team to produce. This is especially true for previously standout ICs whose career reputation is staked on their ability to get things done. They’re nervous those talents won’t translate into management and just try to do things themselves.

Macromanagers are often afraid their team won’t like them or will rebel if they push too hard. Often the highest potential people are promoted early in their careers and as a result their team have similar levels of experience and may have previously been peers, leading to feelings of imposter syndrome.

Simply recognizing what kind of fear is most powerfully motivating your behavior helps a lot. Better yet, explore it with a manager, a mentor, or your team.

Another piece of foundational work is to deeply understand your team. That means knowing them well enough to understand their competence on any given type of project.

In probably the best management book of all time (High Output Management), Andy Grove coined the term task-relevant maturity:

"How often you monitor should not be based on what you believe your subordinate can do in general, but on his experience with a specific task and his prior performance with it - his task-relevant maturity.”

Something I’ve personally observed when doing this exercise: not only is a team member capable at a particular task, but they are often much more capable than I am. There is no clearer sign to back off.

Once you know yourself and your team, consider a framework for when to intervene in a team member’s decision.

The best one I’ve found comes from Keith Rabois, which Delian Asparouhov wrote a great piece on.

How high are the consequences of getting a decision wrong? How much conviction do you have in the right answer? The combination of these two dimensions is a useful recipe for what action to take:

The team needs room to fail, ideally on low stakes decisions. If you don’t have conviction, delegate fully. If you do, let the team roam and consider nudging them along the way.

High stakes decisions are harder. If you do have conviction and the team is headed in the wrong direction, override them. But if you don’t have conviction, you need to work with the team to gather more information until you do.

It is strictly better to be higher on the y-axis more often. Which leads us to our final point on how to find the optimal path: become a context sponge.

The most fundamental job of a manager is to have good judgement, and perhaps the most important ingredient of good judgement is having as much context as possible.

Part of this is about developing expertise in your functional area, which is why the best managers were often elite ICs in a given domain.

But the context you need goes well beyond that. What actually makes this business tick? What are we really trying to accomplish? How are other teams trying to accomplish it? And most importantly, what is actually happening at the company, on the ground, right now?

Jensen Huang (CEO of Nvidia) is perhaps the greatest context sponge of all time. He has an approach he calls “stochastically sampling the system”. Instead of asking for status updates which would be highly filtered by the time they get to him, anyone in the company can email him a list of the “top five things" on their mind. He estimates that he reads 100 of these every day. Clearly this approach wouldn’t work for most people; the point is just how much he invests in building context.

It’s a long path

We are only scratching the surface of one of the hardest learning curves any manager faces. I know that I personally have a very long way to go.

However if you can rapidly identifying your natural tendency and what is driving it, and then begin to take steps to course correct before it creates problems, you’ll be well ahead of most people, perhaps on a new path entirely.

Credits

Thank you to Brian for feedback on this essay.

Great post, Dan. On the topic of micro vs macro management, I learned recently that another dimension at play here is how much managers subscribe to different management theories of what motivates their teams (ex: security vs. vision vs community); here is a short piece on that related topic: https://open.substack.com/pub/waqaswrites/p/choosing-your-your-management-mo?r=jhccc&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

Sent this to a coaching client of mine who was just telling me how overwhelmed he felt by his new management position. He expressed that he felt more comfortable in his active engineering role but felt pressured to take the promotion. Now, he's suffering through the political aspects of his workplace when he'd rather be doing the technical work. I'm hopeful he'll find some advice here that will give him a new perspective! Thank you!