The Software Shakeout: What Is Durable and What Is Not in the Age of AI?

Three weeks ago, investors took a pause from plowing money into AI infrastructure to consider what all those dollars were meant to disrupt, and promptly wiped out $1T in software market cap.

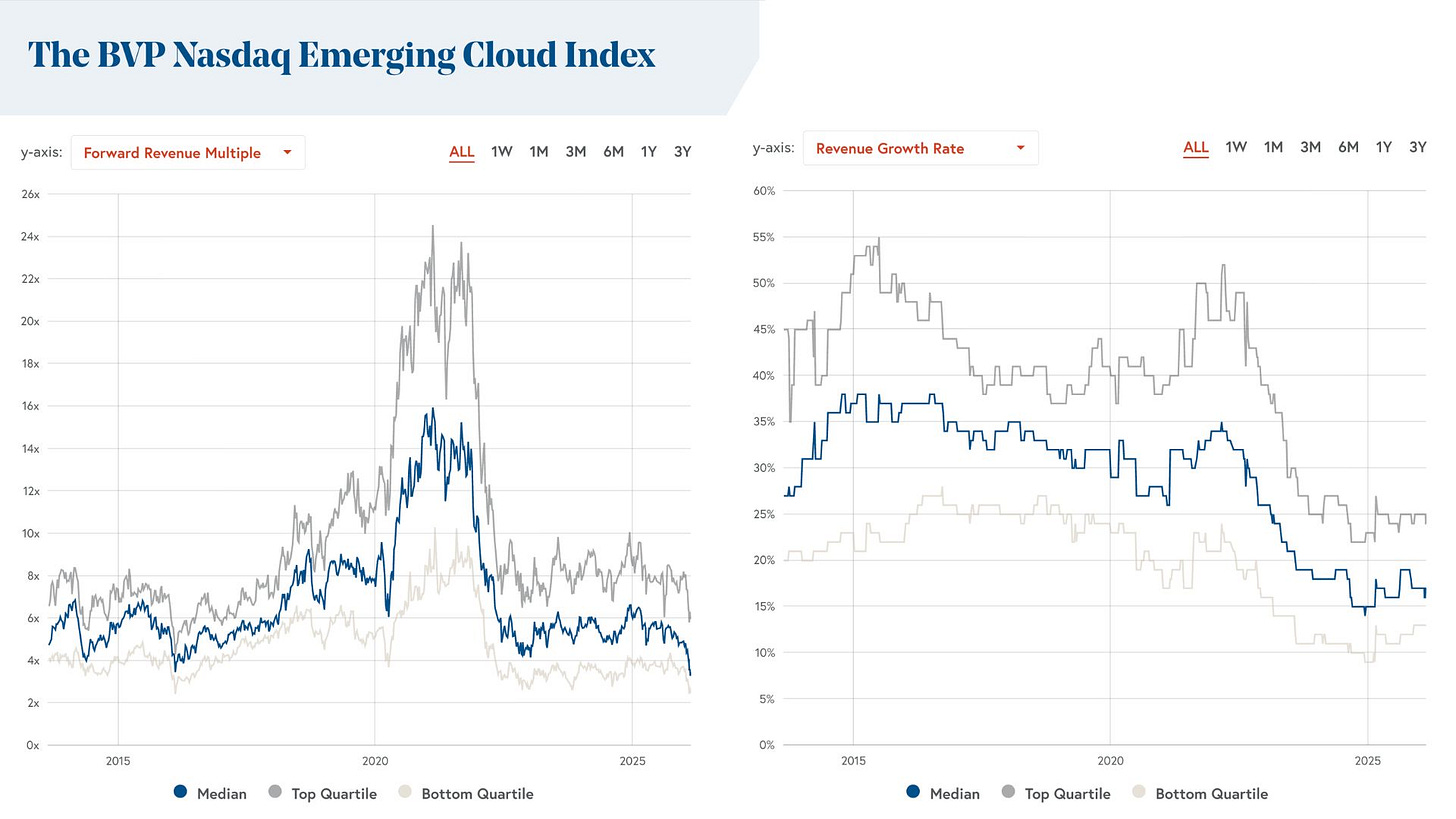

Is it oversold? Unclear. Multiples are the lowest they’ve been in over 10 years, but so are growth rates.

The more important point is that the selling was indiscriminate - everything with perceived exposure got crushed.

We’re now entering the shakeout, where markets try to sort out the true winners and losers. Below is a framework for determining which is which.

What’s the problem?

The threat is not that companies are going to vibe code their own software. Software companies are not their code but the business wrapped around it, the hard parts of which are understanding customer needs, taking the product to market, and bearing the heavy weight of maintenance and customer support.

What will actually happen (as has happened in each past wave) is that existing forms of software will remain, and new and even more valuable forms will get built on top. This is the point Steven Sinofsky made in his excellent essay:

“The lesson here is that whatever the world thought would end just ended up being vastly larger than anyone thought. And the thing that people thought would forever be replaced was not simply legacy but ended up being a key enabler.”

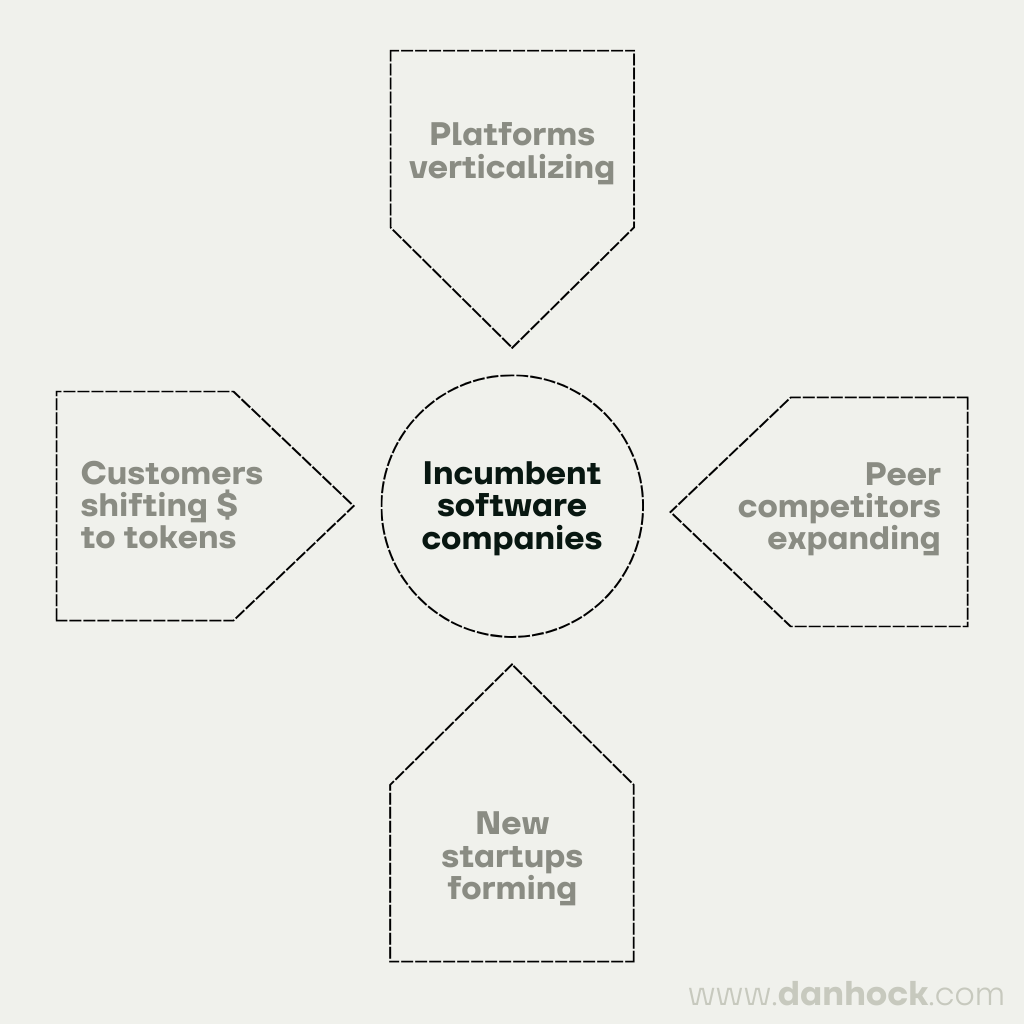

Software as a category will be fine. But it’s unclear if these specific companies will be fine, because there is an explosion of competition coming from every direction.

New startups can now build viable alternatives at much lower cost. The major tech platforms and frontier model providers will try to verticalize into every attractive space. Other incumbent software companies will take advantage of cheap code to move horizontally into new use cases. And customers themselves might now be more inclined to spend their budget on tokens instead of more software.

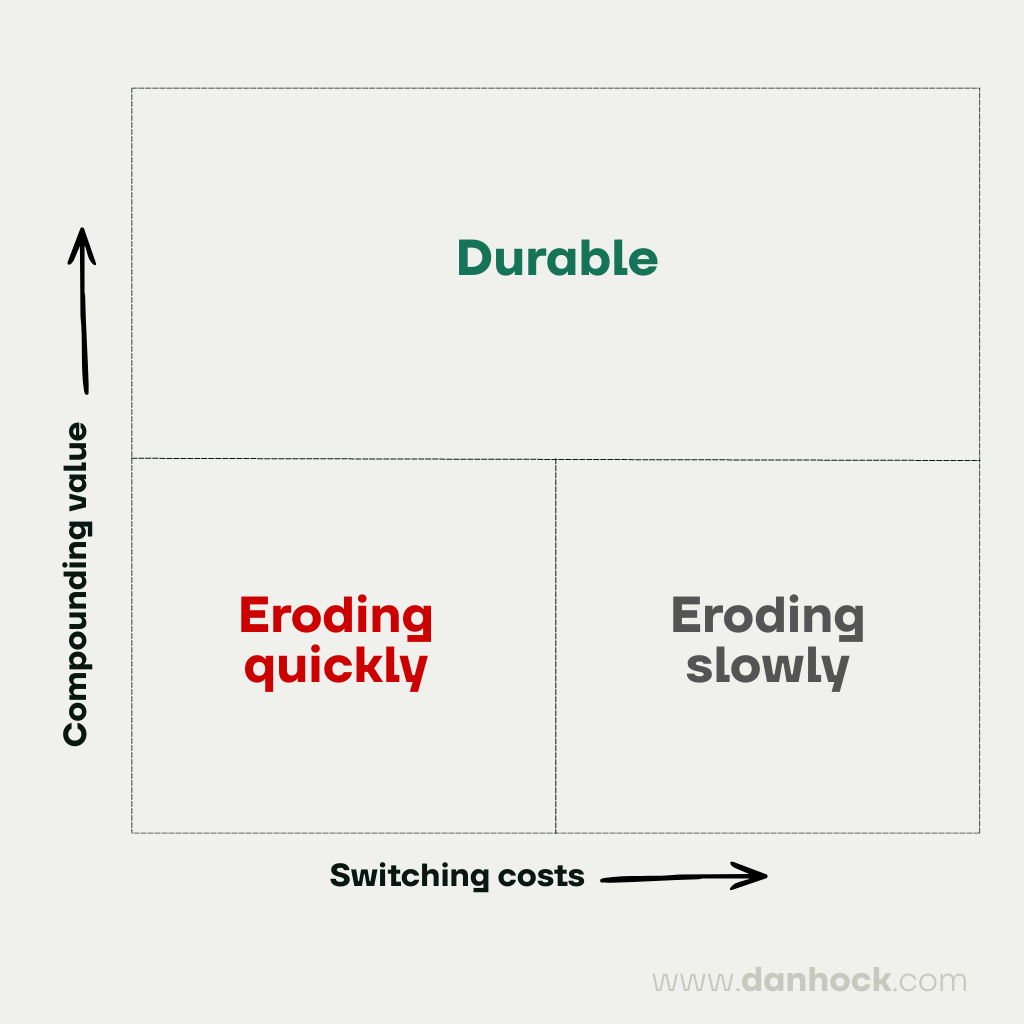

Whether a company survives will come down to two questions:

1. How hard is it for customers to switch to a competitor? This determines how long a company has before it must compete with all of these new competitors on merit.

2. Does the value of the product compound with scale? This is the merit itself. Is the product actually more valuable or lower cost than what the new competition can offer?

Taken together, these dimensions produce three distinct segments. Companies with compounding advantages will prove much more durable. Companies without them will need to adapt their products and monetization models, and switching costs will determine how much time they have to do so.

Let’s break down the drivers of switching costs and compounding value in more detail.

Switching costs

We’ve heard a lot about “systems of record” recently. But this is really just a proxy for switching costs, and increasingly not a very good one as AI brings down the cost of migration. Switching costs are indeed coming down, but there are three things that still matter a lot:

Workflow tax

If a lot of your company has spent a lot of time learning to use a particular UI, it is costly to switch. Some are claiming that this moat is gone because a text box is going to eat that UI. That might be true for some use cases, but not most. For workflows that are sufficiently deep, frequent, or repetitive (which is a lot of them), chat becomes very frustrating very quickly.

Workday and Atlassian have to worry about better products getting built, but they have some time because of how painful it is to get a whole team to switch to something new.

Business disruption risk

If a product manages payments, infrastructure, security, or any other business-critical function, it is much riskier to rip out.

Retailers will think twice before replacing Square, and restaurants will think twice before replacing Toast, because getting it wrong is very costly. This is why historically, new POS companies have carved out market share more by becoming the way new businesses start and less by getting existing businesses to switch. The “theoretical hull speed” of growth is how fast businesses are turning over in an industry, and AI is not changing that very much.

Legal and regulatory risk

You want to rip out ADP for a brand new competitor? Your funeral. Here is what Aaron Levie had to say about it at YC:

“Three years from now there’s going to be a bug… and that bug is going to pay people the wrong amount of money. I don’t want to have to go and call my IT team in the middle of the night to be like, ‘Sh*t, you have to go fix this bug that paid everybody the wrong amount of money.’ I want to be able to go to a company that I know that I can sue if they f*ck up … Because I can’t sue my internal IT team and I certainly can’t sue Anthropic.”

It’s the same dynamic for companies operating in regulated industries. For better or for worse, AI is not going to crack Epic’s hold on the EHR market any time soon.

Compounding value

Some software products get more valuable the more they are used or the greater scale they achieve. This is more important than switching costs, because it determines whether all of this new competition has a chance at competing in the first place.

These forms of defensibility are almost fully intact and, in some cases, strengthened by AI. There are three main ones:

Data effects

In some cases, data is valuable because it is proprietary, typically generated over many years of operating. CoStar has 40 years of commercial real estate data, and unlike the MLS for consumer real estate, there is no public equivalent. ADP has payroll data for 20% of the US workforce. Epic’s Cosmos network has longitudinal medical records for ~80% of Americans.

The other way data effects manifest is when the scale of data directly improves the product experience. Many security businesses are highly defensible for this reason. CrowdStrike processes 100 billion security events a day across all of its customers, making it faster and more effective at identifying threats for any one of them.

AI does very little to erode the advantages of proprietary or high-scale data and will likely help these companies apply it even more effectively.

Scale economies

This is not about the ability to amortize high fixed costs over a growing base of low marginal cost customers - virtually all software companies have that. And you could argue that AI will both lower fixed costs and increase marginal costs, upending the way the economics of software businesses have worked historically.

But some software businesses actually improve their unit economics with scale. This is Stripe having lower costs because its fraud model improves with scale, or AppLovin getting better at pricing impressions as its auction liquidity improves. The cold start problem will be difficult for new entrants in these cases.

Network effects

The most common software network effect has been ecosystem: networks of 3rd party apps and integrations built around companies like ServiceNow and Salesforce. This is weakening in a world where it’s easier for anyone to build apps or integrations around any new product that takes off. So there is some value here, but it’s worth discounting.

But there are other forms that are not impacted, including true cross-side networks (e.g. Shopify Shop Pay in which the product gets more valuable to customers as more merchants use it and vice versa), and cross-company workflows within an industry (e.g. Veeva being used by pharma companies, CROs, and their partners to collectively manage drug development).

How companies stack up

Based on how well they score on switching costs and compounding value, let’s make some (rough) predictions about where different companies belong.

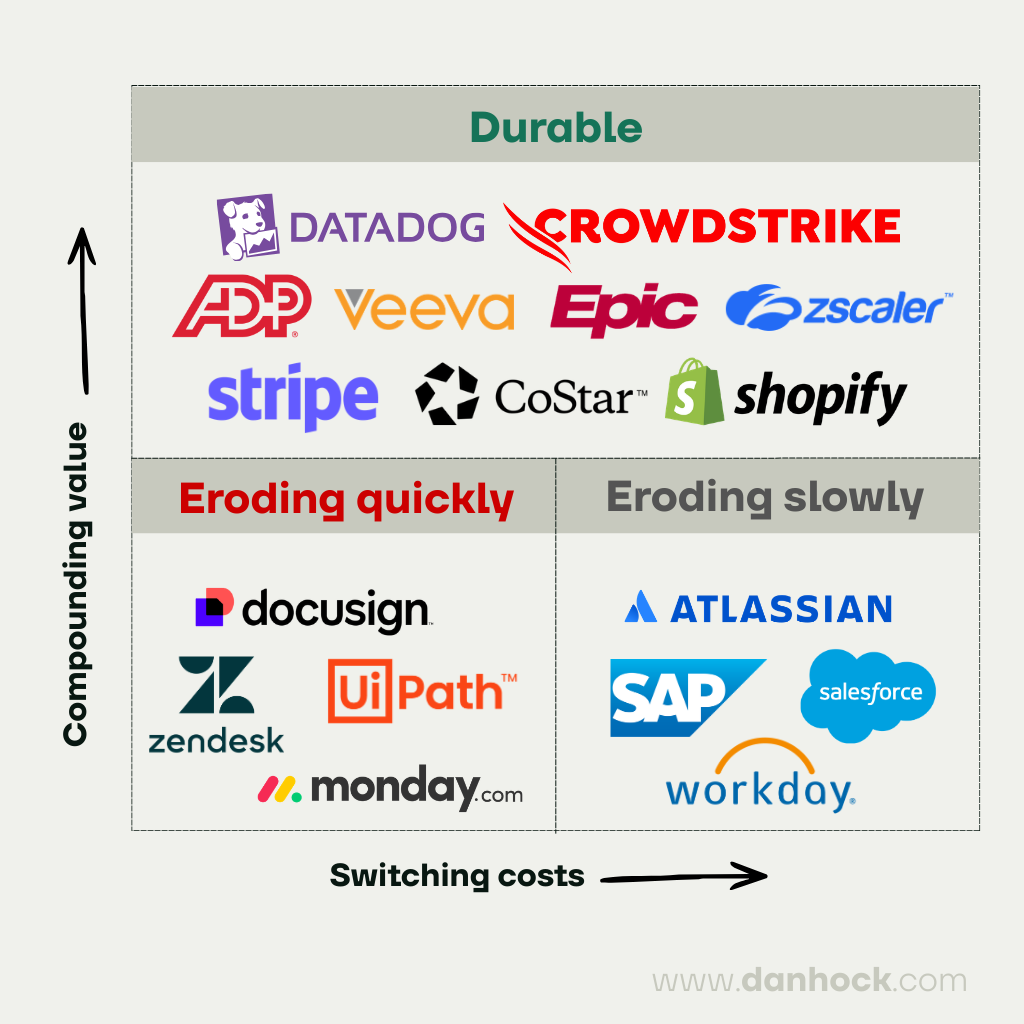

Segment 1: Durable

It matters much less to these companies if there is an explosion of competition, because new competitors start without the network, data, or scale advantages that they have. In many cases, AI will actually be a tailwind as it will allow them to pull forward their roadmaps and further compound their advantage.

The primary thing these companies need to watch out for is adjacent companies that already have access to the data or customer base to bootstrap the compounding advantage, and may now be able to do so more quickly with AI.

Example companies in this segment include CrowdStrike, CoStar, Shopify, Zscaler, Stripe, Datadog, Veeva, Epic, and ADP.

Segment 2: Eroding slowly

These companies have limited compounding advantages. There will be an explosion of alternative products that are comparable, or in many cases better, because it will be easier to build products tailored to narrower segments and use cases.

But they have some time, because it is hard for customers to switch due to workflow complexity, business disruption risk, or legal/regulatory risk. They should be using this time to sprint to improve their offerings and add AI agent functionality on top of the core product.

Example companies in this segment include Atlassian, Salesforce, SAP, and Workday.

Segment 3: Eroding quickly

These companies have neither compounding advantages nor high switching costs, which will lead to a fast bleed of market share as new alternatives show up. They’ll likely need to shift their offerings and monetization model entirely if they want to survive the transition, which is why Gokul Rajaram recently predicted that some companies may need to go private in the coming years if they aren’t already.

Example companies in this segment include Monday, DocuSign, UiPath, and Zendesk.

Where do we go from here?

The market seems to be internalizing these differences in durability to an extent: some of the largest YTD losers have been in more exposed buckets (Atlassian, Monday), and some of the more durable companies have fared better (CrowdStrike, Datadog).

But I expect there is more separation coming. We’ll look at the past 10-15 years as a momentary blip in which the artificial barrier of code scarcity made it possible for too many of these companies to get extraordinary returns. Take away that barrier, and we’ll see who sinks and who swims.

As he often does, Ben Thompson put this perfectly:

The real risk I see for software companies is the fact that while they can write infinite software thanks to AI, so can every other software company. I suspect this will completely upend the relatively neat and infinitely siloed SaaS ecosystem that has been Silicon Valley’s bread-and-butter for the last decade: identify a business function, leverage open source to write a SaaS app that addresses that function, hire a sales team, do some cohort analysis, IPO, and tell yourself that you were changing the world.

Historically, most of the value accrued to the companies that did the very hardest things: scaled networks, improved the structural economics of an industry with data, took on outsized risk, and navigated legal and regulatory complexity. That’s the world we’re headed back to.

Appendix: What is not in the framework?

A number of other dimensions have been proposed for distinguishing between software winners and losers. I think it is worth addressing two of them:

Per-seat vs. outcome pricing: The argument is that AI will put pressure on per-seat models by both reducing the number of seats and creating alternatives that are outcome-based. This is valid, but I would argue that it is mostly downstream of the dimensions outlined above. Most of the examples of durable companies price based on outcomes, and all of the eroding companies price based on seat. Pricing by seat seems to indicate a business model in which value does not compound with scale and in which ROI is harder to measure, so seat-based monetization is the only option.

Hardware: Companies with hardware will be more defensible both because AI helps less with the creation of new devices and because they contribute to customer stickiness. This is valid, and I only excluded it from the framework because (1) it’s not all that common (roughly 10% of the 68 companies in the EMCLOUD index) and (2) most of the companies with hardware are already predicted by the framework to be durable.

Credits

Thank you to Zach Grannis for his feedback on this essay.

Sources

Essays

10 Years Building Vertical Software: My Perspective on the Selloff - Nicolas Bustamante

Rebuttal to Nicolas - @atelicinvest

AI Agents to Boost Productivity and Size of Software Market - Goldman Sachs

Build vs. Buy - Jamin Ball

Death of Software. Nah. - Steven Sinofsky

In Defense of SaaS - Finbarr Taylor

Is SaaS Dead? No. But One Thing Is Clear: It’s Unstable. - Jason Lemkin

Microsoft and Software Survival - Ben Thompson

SaaS Isn’t Dead. It’s Worse Than That. - Michael Bloch

Shopify Earnings, Shopify’s AI Advantages - Ben Thompson

Time’s Up for SaaS (Grow Faster or Vanish) - Alex Clayton

The Agent Will Eat Your System of Record - Zain Hoda

The Crumbling Workflow Moat: Aggregation Theory’s Final Chapter - Nicolas Bustamante

Why that $2 trillion software stock wipeout didn’t derail the AI bull market - Jim Edwards

Very convincing framework. It was interesting to hear Jared Sleeper make the case on Odd Lots that Docusign’s shockingly high head count comes from hidden operational and legal/regulatory complexity that can’t be vibe coded. Trust is also a scale network effect.

I really like the ADP example. I used to work for them in IT audit and compliance. One issue and concern is that there is more to software than just writing some code. The security and compliance aspect and the integrity of the company is a factor that will make some tools unmarketable to smart businesses. The risk is the unsophisticated businesses that uses a poorly implemented third-part tool - the risk is not something people talk about. Vibe coding and letting AI agent run autonomously does not have the foundation safety nets in place. It's going to be a mess and the bad actors are just waiting.