The internet killed general-purpose products. AI will bring them back.

Department stores were a general-purpose product: pretty good selection, pretty good prices, pretty good quality, pretty good shopping experience.

But being pretty good at many things is not a stable equilibrium, because most customers only care about one or two of them.

“In business we often find that the winning system goes almost ridiculously far in maximizing and or minimizing one or a few variables – like the discount warehouses of Costco.” - Charlie Munger

Costco (and Walmart and Temu and Shein) won on price. Amazon won on convenience. Nordstrom and D2C brands won on quality. Independent local retailers won on experience. They collectively stole market share until there was none left, and department stores died.

This is not just about retail. General-purpose products are dying everywhere. In this essay we will cover:

Why every industry is following the same pattern

Two more examples of this trend from media and education

Why AI will be the technology that finally reverses the trend

Why is this happening?

Many people describe what is happening as the “barbell” effect. The theory is that in every industry, both very large companies and very small companies win, and everything in the middle dies.

This theory is incorrect, or at least incomplete.

Michael Porter has a series of tests of good strategy which do a better job of articulating what is really happening. He said that in order to win, a company must have:

A distinctive value prop: a unique benefit to customers

A tailored value chain: a company designed to deliver those benefits

The ability to make trade-offs: choosing what to do and what not to do

The first two criteria are what he called “the core” of strategy. Pick a consumer value prop, like convenience, then build a business fully optimized to deliver it, like Amazon.

The third test explains why Amazon can’t take over the entire retail market. It’s not just difficult to provide everything customers want simultaneously; it’s impossible. To deliver the highest convenience, Amazon had to build a supply chain optimized for delivering small quantities of products very fast, which is more expensive than what Costco or Temu built. It has to stock as many products as it can, which means it can’t vet quality or protect the customer experience as well as Nordstrom or D2C.

The result is a predictable pattern as industries mature. They start with general purpose products in the middle. Then a new technology allows an incumbent or a startup to deliver better on a specific benefit. When others see it is working, a new cluster forms around it. Each company gets better and better at optimizing its chosen strategy. The clusters become increasingly tightly packed and farther away from each other. Anyone who tries to stay in the middle dies.

Two more examples:

Media

One thing people want from media is for it to cater to exactly their specific interests and tastes. That’s YouTube and TikTok.

Another thing they want is shared cultural experience. Something to laugh and cry and bond over with friends and family. This segment is thriving: Hollywood movies are increasingly high budget and focused on stories and characters everyone already knows. Paris hosted the highest rated Olympics ever. The NFL had 70 of the top 100 broadcasts last year.

Some people want to feel smart, intellectually stimulated, high status. Prestige TV (Succession, The White Lotus) pushes the boundaries of production quality and subject matter to meet that need.

Sitcoms and variety shows were once the general-purpose products of this industry. Now they’ve been relegated to the much smaller use case of mindless or “passive” entertainment.

Education

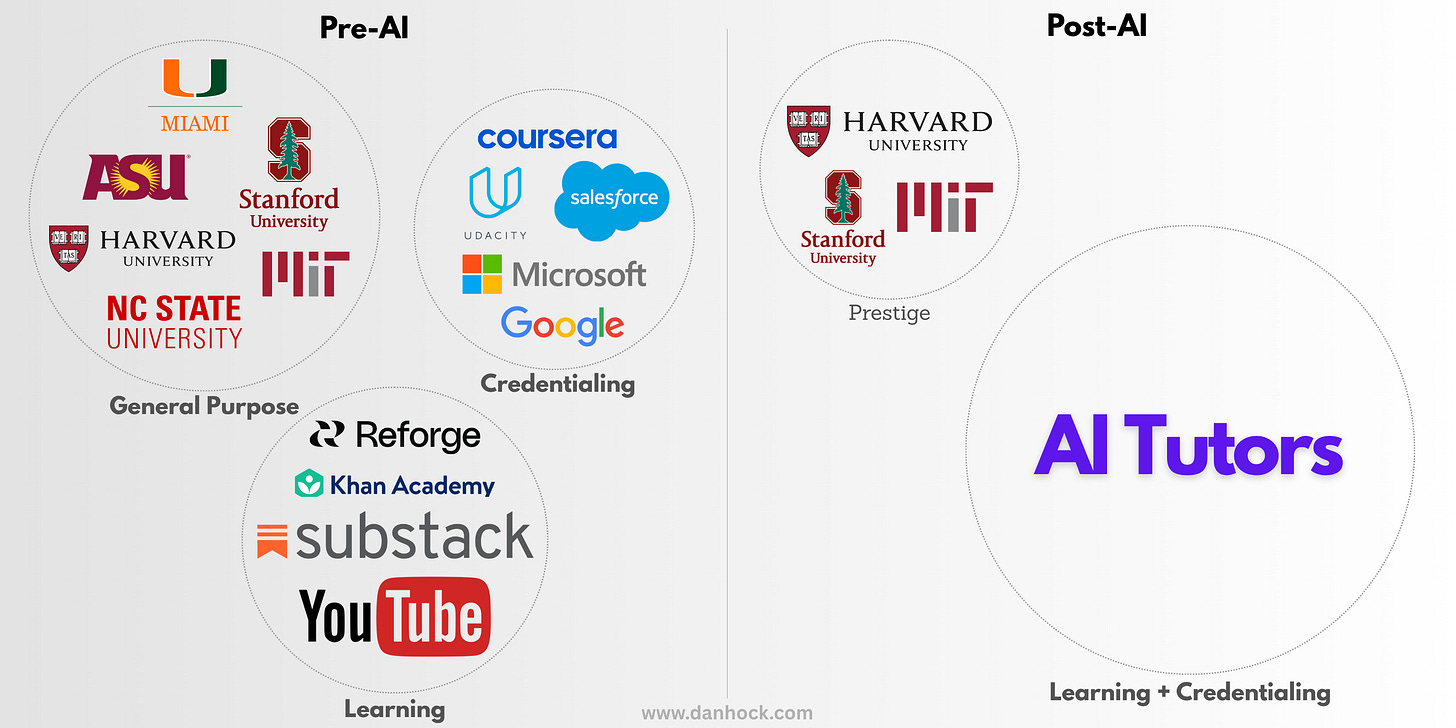

Universities are a general-purpose product. They started losing share in 2016, a trend that will accelerate because most of them do a mediocre job at many things.

One thing universities offer is prestige: the ability to be surrounded by elites and become one by association. This will continue to be solved by universities, but probably only the top 10 or 25 of them in the US that actually do it well.

Another is credentialing: proving you can do a job to potential employers. Online programs and employers themselves will be able to do this much more effectively.

And of course there is actually learning things. Cohort-based programs, Youtube, and Substack are slowly winning at this.

What comes next?

In every story so far, the internet removed a bottleneck in distribution, allowing new types of products to work and further decentralizing the industry around distinct value props:

The internet removed the physical constraints on how much inventory you could put in a store, enabling Amazon to build the “endless aisle”

It removed the constraint of 3-4 big TV networks with a limited amount of programming and allowed new providers to “go over the top” with many more kinds of content

It removed the constraint of the physical college campus, allowing students to learn in many new ways

AI will not just impact the way products are distributed, but the nature of products themselves.

AI’s core strength is the intelligence and flexibility to tailor outputs to each customer’s individual needs. This will enable products that can be great at multiple value props simultaneously, causing a re-centralization of industries around fewer clusters led by new, massive general-purpose products.

In retail, the clusters we see today around quality and convenience will collapse back into one. The ability to offer a massive selection without undermining quality is a ranking and personalization problem. If Amazon could deliver exactly the right product for each customer and use case, they could protect the high-end experience for some customers without eliminating the massive selection for others.

To achieve this, e-commerce products may start to look more conversational, gathering more input on exactly what each customer is looking for and using this to deliver more tailored results.

In media, platforms will emerge that can take any user prompt and create bespoke video, audio, and text catered entirely to that person’s tastes and interests.

That will clearly do the job that YouTube or TikTok are doing, but it could also swallow the passive and prestige clusters as well, because it will be able to achieve similar or better production quality at virtually no marginal cost.

The only cluster that these products will find it hard to crack is shared cultural experience, because the whole point is that everyone else is watching it too. However you could imagine this need ultimately being served by pieces of content that were originally generated for individuals going hyper viral (a dynamic we’re already starting to see with TikTok).

What happens in education might be the most extreme of all. Superintelligent AI tutors will provide 1:1 learning catered entirely to each person’s goals, interests, and learning styles. They will generate video, audio, and text on demand that is massively better than what universities, online courses, YouTube, or Substack can provide today. And they will know exactly how far each learner has progressed, so they will become much better at credentialing as well.

Prestige is hard to address, because the whole point is that most people can’t have it. But it’s not hard to imagine a world where there is a small set of elite universities for a very narrow audience, and AI super-tutors for everyone else.

In each industry, Porter’s 3rd test of strategy starts to collapse. There will no longer be trade-offs between things like convenience and quality or between personalization and production value. A new kind of product will emerge that can be great at many things simultaneously. Welcome back to the era of general-purpose products.

Thank you to Brian Balfour and Zach Grannis for their feedback on this essay.

"Prestige is hard to address, because the whole point is that most people can’t have it."

Prestige itself could be disrupted. If AI Tutors deliver skills that make the "best students" more effective and productive, having a prestigious degree could be seen as superfluous and less valuable, akin to a mythical signal of skill, similar to a pre-moneyball baseball player who is graded largely by how they look rather than what they can produce. The skill and prestige of "getting into Harvard" probably isn't that valuable in real-life pursuits, despite what we've been led to believe.

Great article and analysis! Lots of useful framing.

Great essay. It had me thinking about whether AI bringing back general-purpose products through personalization makes it harder for small companies to stand out with new ideas and shape unexpected needs.